April 14, 2010

Worst Week Ever

Posted by Finn under Number Crunching, Recent Developments | Tags: Atlanta Braves, Florida Marlins, Houston Astros, Texas Rangers, Toronto Blue Jays |1 Comment

April 3, 2010

In 2010, The Best Offense is a Good Defense

Posted by luke under Number Crunching, Recent DevelopmentsLeave a Comment

When Michael Lewis wrote Moneyball, a handful readers misinterpreted its meaning in a variety of ways. The truly dense individuals interpreted the book as an extended argument for Billy Beane’s prowess as a General Manager. Others simply read it as a case for On-Base Percentage as baseball’s most important and underappreciated statistic. The book’s point, of course, was to demonstrate how to exploit certain traits that had been undervalued by a particular market, using baseball as a case study.

In 2010, OBP is no longer underappreciated. Even the casual baseball fan often places just as much importance on OBP as he does on batting average. Cristian Guzman? Sure, he hits .300, but the guy never draws a walk! Adam Dunn? Okay, the average is ugly, but look at that .383 career OBP. That’s why he’s making $12MM this season.

No, OBP has long been replaced as the statistic of choice by Moneyball believers. Their newest focus was hardly a secret either, and this offseason accentuated it more than ever. Accentuated it to the point where it now seems like every major league franchise is in on the secret. Which begs the question: can teams still identify bargains in the market by placing a premium on a player’s defense?

—

I remember watching baseball as a kid. Even when I was 6 or 7, I loved statistics. I was just unnaturally into them. I’d even go so far to say that If I’d known about OPS, I would’ve loved it. Sure, the ones I typically committed to memory and focused on most were the basics: AVG, HR, RBI, and so on. Every single one of the non-pitching ones was offense-specific though. Defensive stats? I knew errors, and maybe fielding percentage, but I certainly wouldn’t knock a player for having a fielding percentage of .970 instead of .985.

The irony is that even Moneyball subscribed to this approach, to a certain extent. Once the A’s had acquired their high-OBP talent, they were content to play them anywhere on the field. Jeremy Giambi in the outfield, Scott Hatteberg at first base. Defense was marginalized, a talent far less important than the ability to get on base and hit for power.

In retrospect, it didn’t really make sense. I suppose the assumption was that if you’re a good enough ballplayer to make it to the big leagues, you can catch and throw a ball. The players who were better at doing these things, and who could cover more ground while they did them, couldn’t be that much better than the players who were merely adequate fielders, right? Well, not really.

When the sabermetric revolution tackled defense, another blatant irony was revealed: those players with few errors and high fielding percentages? Not necessarily great fielders. After all, a player that has the range to get to more balls is going to commit a few more errors than those jerks who just let them fall in for hits.

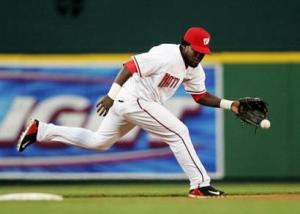

So, the invention of UZR (Ultimate Zone Rating) has placed an all-new importance on defense. You think that the Mariners were so eager to lock Franklin Gutierrez up to a long-term deal because of his .283/.339/.425 slash line in 2009, or might it also have had something to do with the fact that his UZR was an astounding +29.1 in center field? Yeah, his defense alone saved the Mariners 29 runs. Similarly, the Rays and Rangers, respectively, may not have been as patient in allowing B.J. Upton and Elvis Andrus to play every day last season if it weren’t for their defense. B.J. hit an ugly .241/.313/.373, but posted a UZR/150 of +11.8 in center. Andrus? A +11.7 UZR/150 at shortstop to go along with .267/.329/.373.

This year’s free agent class drove home, more than ever, that defense is a crucial aspect of every team’s evaluation of a player. Consider these examples:

Alex Gonzalez, SS (+10.5 UZR/150)

After posting a significantly above average UZR/150 for the third straight year, Gonzalez was signed extremely early in the winter by the Blue Jays, even earning a starting gig with them.

Chone Figgins, 3B (+18.8 UZR/150)

Despite being decidedly below average at nearly every other position he’d played, Figgins found his niche defensively over the last two seasons as the Angels’ third baseman. Figgins has the added bonus of being a strong on-base guy, reaching at a .386 clip over the past three years, but, with just nine homers over that same stretch, there’s no way he gets $36MM from the defense-happy Mariners if not for his prowess at the hot corner.

Adrian Beltre, 3B (+21.0 UZR/150)

Beltre represents perhaps the most extreme example from this year’s free agent class of strong defense improving a player’s worth. This guy was awful offensively last year, hitting just eight homers and OPSing .683 in 477 plate appearances. Since signing with Seattle, his OBP is only .317, and even his power has been mediocre — he’s averaging 24 home runs per 162 games. So why did a bidding war break out this winter for his services, culminating in Boston signing him to a one-year, $10MM(!) deal? Simple: his defense.

Johnny Damon, LF (-12.1 UZR/150)

Now let’s go the other way. Damon’s value was surely hurt this offseason by offensive numbers that were inflated by the new Yankee Stadium. However, his defense certainly didn’t do him any favours. Even heading into the offseason, many Yankees fans were set against bringing back both Damon and Matsui, since they couldn’t imagine one of the two playing in the outfield all year. When the Tigers eventually signed Damon to a one-year contract worth $8MM, it was considered an overpay. Remember, Damon hit .282/.365/.489 last year — Beltre, who signed for $10MM, hit .265/.304/.379.

Jermaine Dye, RF (-24.5 UZR/150)

And finally, my favourite example of the value of defense in 2010. Dye, a guy who has averaged 33 homers per season since 2005 and who hit 27 in a down year last season, is still without a job. Now, it’d be unfair to blame defense entirely. Dye’s contract demands are probably still unreasonably high. But is there any way a player like this remains unsigned on the eve of Opening Day five years ago? His near-league-worst UZR/150 (hat tip to Brad Hawpe for being an even worse defender than Dye) has National League teams scared of signing him and playing him in the outfield. So scared, in fact, that the Washington Nationals, who probably could afford him, are currently using a right-field platoon of Willy Taveras and Willie Harris. Willy Taveras and Willie Harris. Think about that.

—

So, UZR is, at present, what OBP was when Moneyball was released: a statistic that had been exploited for a few years, but was becoming mainstream enough that it was increasingly difficult to use it for bargain-shopping anymore. The longer the Jermaine Dyes of the world remain unsigned, the more blatant the league-wide awareness of defensive skill is.

This leaves the question: What’s next? With an unprecedented amount of in-depth statistics available to even the casual fan, what one can a Major League General Manager possibly look at when he goes bargain hunting? Until they come up with a statistic to measure heart, the answer remains unclear.

July 2, 2009

What’s Eating Khalil Greene?

Posted by Finn under Number Crunching, Recent Developments | Tags: San Diego Padres, St. Louis Cardinals |Leave a Comment

Prior to the 2005 MLB season, Baseball Prospectus had the following to say about Zack Greinke, a 21-year-old starting pitcher for the Kansas City Royals:

With apologies to Jon Landau, we have seen the future of pitching, and his name is Zack Greinke. There are two sets of opinions on Greinke. There’s the camp that thinks all the talk about him being the most unique young pitcher of our generation is overblown hype. Then there’s the camp of people who have seen him pitch.

Greinke, they would go on to say, possessed not only an All-Star caliber arsenal, but also a crafty pitching style which was perhaps unique in the game, especially among pitchers his age and with his ability. Though he could throw a mid-90s fastball, he preferred to sit in the upper 80s, sacrificing speed for impeccable control. He was prone to quick-pitch batters to catch them off-guard, teasing them with a slider or cutter before making them look foolish with a big sweeping curveball that dipped into Tim Wakefield territory.

That spring, the Royals decided that they could squeeze considerably better results out of Greinke — he’d posted a 1.17 WHIP his rookie year, but struck out “only” 6.21 batters per nine innings — if they tinkered with him a little bit. And so they did, encouraging him to throw the ball harder and eschew some of his former style. His WHIP ballooned to 1.56, thanks to a walk rate that was nearly twice what it had been in his rookie season.

Just 22 years old, Greinke appeared broken. That winter, he was diagnosed with a “personal mental health condition.” The Royals placed him on the 60-day DL and he essentially disappeared for the 2006 season, returning later in the year to make starts in AAA after undergoing treatment for what would eventually be revealed as Social Anxiety Disorder.

Just 22 years old, Greinke appeared broken. That winter, he was diagnosed with a “personal mental health condition.” The Royals placed him on the 60-day DL and he essentially disappeared for the 2006 season, returning later in the year to make starts in AAA after undergoing treatment for what would eventually be revealed as Social Anxiety Disorder.

Greinke would essentially reemerge as a starter at the beginning of the 2007. He was throwing harder, and from a statistical standpoint, matched the success of his rookie season. In 2008, he was even better; still just 24, his return had gone largely unnoticed by the national media. That wouldn’t be the case for much longer: Greinke set the baseball world ablaze at the beginning of the 2009 season, and between the end of 2008 and beginning of 2009, he went 38 straight innings without allowing a run, capping the streak off with back-to-back complete game victories. At 10-3 with a 1.95 ERA and 114 Ks in 115 innings, he’s the early favorite for the AL Cy Young Award.

What, if anything, does this all mean?

Greinke’s condition — Social Anxiety Disorder — is psychiatric condition that affects, by most estimates, approximately 5% of the adult population in America. Usually brought on by situations of intense (real or imagined) social scrutiny, it’s characterized by excessive sweating, nausea, stammering, and in some cases severe panic attacks. It can be specific (only brought on by certain situations) or generalized. He was a highly-touted young prospect who came to the majors, encountered intense stress, and essentially wilted. He disappeared from the game, underwent some form of treatment, and then reemerged the dominant force many imagined he’d become in the first place.

The problem here, of course, is that this all sounds very wishy-washy to the majority of those who care to watch and have an opinion on the matter. During that difficult 2005 season, Greinke was paid about $330,000 to pitch relatively poorly for the Royals. He was paid money — a lot of money, by most everybody’s standards — to play a game, a beautiful game, a cherished American game. Wasn’t that good enough for him? A normal person wouldn’t be given reprieve by their boss for feeling anxiety — why should this guy, rich as he was, and playing a sport where we expect men to be men, be afforded such a fairy-pants luxury?

The criticism was, and still is, very easy: grow up, you big baby, and deal with your failures, just like the rest of us normal folk do. If you can’t take the pressure, you don’t belong; go push papers back in Orlando.

Then, there are the results.

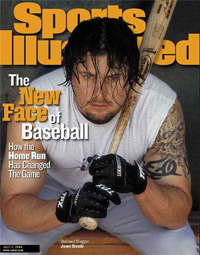

Zack Greinke, snowflake that he was, is embarrassing your favorite hitters right now, and at 10-3 might be the best pitcher in the American League. He was featured — knock on wood — on the cover of Sports Illustrated earlier this year, and hasn’t skipped a beat, even with the national spotlight now officially on him. So can you really say that whatever happened, whatever he took time away from baseball to do, whatever he’s currently doing to help himself cope with the pressure, is all some big scam? Some fraud perpetrated by the oversensitive clinical zeitgeist that’s wrapped the country in its big pink Snuggie? Or, heaven forbid, was Zach Greinke cured?

—

Though he’s something of an afterthought in the minds of most baseball fans, many will recall that in the first half of the decade, Khalil Greene was considered a very good prospect. The Clemson product was drafted by the Cubs in the 14th round of the 2001 draft, but elected to return to school to complete his senior year. The decision certainly worked out: he posted a crazy 470/.552/.877 line in 2002, offensive stats which accompanied by his excellent defense at shortstop earned him USA Baseball’s Golden Spikes Award and a first-round selection by the San Diego Padres, who gave him a $1.5 million signing bonus. He finished out 2002 playing for A+ Lake Elsinore, posting an .893 OPS alongside then-teammate Xavier Nady.

Greene was a September callup in 2003; the Padres, lacking a better option at short, opened 2004 with Greene as their starting shortstop (incumbent veteran Ramon Vazquez was sent to the bench). Batting 8th in a lineup that included Sean Burroughs, Phil Nevin, and Ryan Klesko, Greene had a solid rookie season and managed a .795 OPS in 139 games. His defense was not spectacular (.965 FPct was fifth-worst in the majors) but he stood out in his rookie class, taking home second honors in the Rookie of the Year voting behind former teammate Jason Bay.

Then his career basically stalled. His 2004 season started a four-year period during which Greene batted a pedestrian .256 with a .313 OBP while averaging just 497 plate apperances per season thanks to many handfuls of minor injuries. He did showcase decent power, especially on the road: he hit 15 homers in each of his 2004, 2005, and 2006 seasons, two-thirds of those homers coming away from Petco’s power-stifling confines. In 2007, Greene finally logged 600+ appearances at the plate, popping 27 homers to go along with his a tepid .254 average. Almost half of his 2007 home runs (44%) came at Petco.

.256 with a .313 OBP while averaging just 497 plate apperances per season thanks to many handfuls of minor injuries. He did showcase decent power, especially on the road: he hit 15 homers in each of his 2004, 2005, and 2006 seasons, two-thirds of those homers coming away from Petco’s power-stifling confines. In 2007, Greene finally logged 600+ appearances at the plate, popping 27 homers to go along with his a tepid .254 average. Almost half of his 2007 home runs (44%) came at Petco.

There were some underlying signs of a gradual change in approach. While he spent those years battling cold stretches by tinkering with his stance, his selectivity at the plate waned: the percentage of balls outside the zone that he swung at increased with each passing year. Of those bad pitches, he made contact with about half. There are two types of hitters who can sustain success while swinging at high percentages of bad pitches: those who make up for it with tons of power (like Alfonso Soriano), or those who are just exceptionally good at hitting bad pitches (like Juan Pierre). Greene, despite his modest HR totals, was neither of those things.

In 2008, the bottom fell out. After parlaying those 27 homers into a 2-year $11m deal with the Padres, his average plummeted to .213 while his HR rate dropped over 40% from 2007. Greene’s discipline at the plate suffered further, and he struck out five times as often as he walked.

July 30th of that season would be his final game in a Padres uniform. Playing shortstop and batting 8th against the Diamondbacks, Greene grounded out twice to the left side of the infield – one going as a double play – and then struck out swinging against Dan Haren in the 7th, his 100th K of the year. Following that at-bat, he returned to the clubhouse and punched an equipment storage container, fracturing his hand in the process. He was replaced in the game by Edgar Gonzalez; the Padres, trailing 5-3 at the time, would go on to lose 7-3.

An ugly back-and-forth between Greene and the Padres ensued; never one to be particularly comfortable in the spotlight, the shortstop was now involved in a public battle over his salary, which the team attempted to recover after Greene’s self-inflicted injury ended his season. Already in salary-dumping mode, the Padres had all the more reason to move Greene; they traded him in December to St. Louis for bizarro rightie Mark Worrell.

At this point, Greene is by no means a newcomer to the game; after breaking into the bigs in 2003 at age 23, he’s logged almost 2,800 plate appearances between the Padres and the Cardinals. His career line of .245/.302/.423 is unsightly, and has not earned him much sympathy in the month since this story has broken. Where, many ask, was this anxiety when he was doing well? The more obvious question to me is: why now? It’s been a very up-and-down ride for Greene, with an emphasis on the down: random variance in production is to be expected, but he’s made frequent habit of plummeting below the mendoza line. Could his slumps hold any clues to his breaking point?

There have been 18 points throughout Greene’s career at which his 10-game average has cratered below the .150 mark. Three of those “craters” were also associated with dips in his 20-game average below .150. Though Greene, prone to these bouts of poor play, has been streaky throughout his entire career, these prolonged extreme dips in his production are a relatively new phenomenon. He’d always bounced back to mediocre before; now, he’s really wallowing.

Two of these three dips — those occurring on 7/18/2008 and 5/27/2009 — seem to be closely tied to Greene’s apparently exceptional levels of anguish. Two weeks after the 7/18/2008 crater was when Greene punched the storage locker. The timing there did seem off: Greene had actually raised his average a bit prior to that game, and his 20-game strikeout rate (then 3.4 AB/K) was not too far below his career rate (4.6 AB/K). Still, it was obviously out of frustration over his poor play that Greene lashed out, and it can be seen that he was playing exceptionally poorly at that time.

The second bout of problems, his being placed on the DL with an “anxiety disorder,” occurred around the 5/27/2009. Not only was he playing some of the worst baseball of his career, he’d also been basically relegated to a utility role on LaRussa’s squad, and had been the subject of some trade rumors. This was all too much for Greene, who actually tried to come back , went 5-25 with 3 HR, and then was returned to the DL with Social Anxiety Disorder.

What about his first foray into Batting Average Hell? That occurred at the end of the 2006 season, when he missed time with a lingering finger sprain (he sprained it swinging a bat, then was hit in the hand by a Brandon Backe pitch when he attempted to return to the lineup after a few games off). The sprain severely hampered his offensive output: the Cardinals were simply killing themselves with Greene in the lineup, as he went 1-23 with 10 strikeouts to finish the 2006 season. We can give him the benefit of the doubt: this particular extended slump appears to have been related to the finger injury (he’s missed 155 games over his career due to injury, an amount which encompasses almost a full season’s worth of games; actually, Greene has never played 155 games in any season).

It’s somewhat absurd, of course, to pretend that still-mysterious mental disorders can be studied in any meaningful way by looking at such crude statistical measures. This is what we have, though, and aside from a very loose correlation, we can’t make any meaningful armchair diagnoses. So did Greene have these problems prior to arriving in St. Louis? What, if anything, set him off?

It’s somewhat absurd, of course, to pretend that still-mysterious mental disorders can be studied in any meaningful way by looking at such crude statistical measures. This is what we have, though, and aside from a very loose correlation, we can’t make any meaningful armchair diagnoses. So did Greene have these problems prior to arriving in St. Louis? What, if anything, set him off?

It’s entirely possible that nothing really changed in Greene. We don’t know if he approached the team, or the team approached him: it’s entirely plausible that someone on staff thought they saw something troubling in his demeanor and set the process rolling him- or herself. The organization might be slightly more inclined to notice these things: Greene’s current teammate, Rick Ankiel, who famously imploded during the 2000 NLCS in front of a national television audience and whose setbacks were so severe that he had to abandon pitching altogether, has basically recovered from a far more public nightmare.

Complicating matters is the fact that we can’t really say for sure who Greene is as a player — and neither can he. He had an accomplished college career, but in truth, has never excelled at any professional level. Is his poor hitting caused by anxiety, or is his anxiety caused by poor hitting? Many have made careers of being slick-fielding offensive failures; does Greene’s embattled exterior mask the innards of a good-glove-no-stick infielder who’ll occasionally run into 10-20 homers per season? It’s possible that he holds himself to higher standards than he’s destined to ever achieve, and that he’s basically been unable to cope with what he is.

—

This all sounds somewhat strange, this business of players having to understand things like value, much less comprehend and accept their own value. Once upon a time, if a little rocket-armed right-hander couldn’t handle pitching games all year, he was a failure, a weakling, the stuff of boorish clubhouse jokes strung up on beer-stained breath. Then someone came along and decided that maybe there should be such a thing as a relief pitcher, and that maybe some of these kids who couldn’t throw 200 innings could throw 80 and be really, really good at it. Suddenly, the reliever was born, and from that radical thought, the closer. Now, some of the most feared and respected pitchers in the game — Joe Nathan, Jonathan Papelbon, and the best relief pitcher in baseball history, Mariano Rivera — are in fact failed former starters. Sixty years ago, Mariano Rivera is just a dumb fisherman who couldn’t hang with real men. Now, he’s a legend.

Often, their shoulders simply couldn’t handle the load. It’s easy to forget how absurd the notion of pitch counts once was; now, if you aren’t up on keeping your pitchers healthy, you’re seen as an idiot. Some still disagree with the concept of protecting pitchers from excessive physical stress, but those stalwarts are very much dying off. And it’s not just pitchers. It used to be that injuries were seen as a sign of some nonspecific “weakness” in a person’s fortitude. Now, the diligent prevention of them is big business. Ignoring a physical injury isn’t a sign of strength, it’s a sign of stupidity, one that costs teams ballgames and millions of dollars (look at what some are whispering about the Yankees’ treatment of A-Rod’s injury).

Mental disorders are essentially uncharted territory. If Cubs fans could go back in time and collectively give Mark Prior’s shoulder a hot, therapeutic massage with some garish pink vibrating implement, they absolutely would, pride and toughness be damned. It is difficult to say exactly what the difference is between a physical issue, like a weak shoulder, and a mental issue, like a weak sense of self-worth. We can test for the former, and while some say we can test for the latter, it still doesn’t feel right to us. This might be because it’s already been so embraced — and almost certainly abused — in other areas. Suddenly, common mental disorders like SAD and ADHD aren’t legitimate medical conditions, they’re excuses used by lazy parents to shield their coddled sons and daughters from the altogether normal pressures of childhood. We see a ballplayer claiming to have the same problem, we make a connection; this guy is just making excuses. It’s totally natural. But is it right?

Football players are famously given Wonderlic tests during their young careers. Most would bluntly argue that the tests are designed to see if that big, hulking quarterback is smart or an idiot; mental deficiencies are cutely expected and dealt with in sports where men are often measured by the force with which they are able to hurl themselves about. Really, they test intelligence, logic, and decision-making abilities, or they’re supposed to. Even then, a poor Wonderlic score is not a sign that a person isn’t cut out to play football.

It’s not difficult to see a world where baseball teams start paying attention to this sort of thing, assessing both mental quickness and fortitude alongside their physical counterparts. While society can’t even really decide what a person’s mind “should” be like (because really, there’s no answer to that question), teams are already paying attention. They’re The “Disabled List” has been somewhat radically re-purposed to handle players dealing with stress- and anxiety-related issues; in addition to Greene, Dontrelle Willis, Joey Votto, and Ian Snell have all thusly missed time this year.

It will be a very long time before baseball considers a chronic personality issue in the same way they treat a chronic hamstring issue, but it’s reasonable to expect that it will happen. Until then, it’s worth plenty of discussion. We’ll never stop worshipping our favorite players, because god dammit, we want to. That’s what makes all this steroid business so troubling: you’re making it too damned hard for us to love you. And so we may as well ask ourselves what we really want from these guys. We are willing to pay you all sorts of money so that we can sit around and watch you play baseball. Most of us would like you to do this without taking anabolic steroids or HGH or any other dubious creams, ointments, pills, or injections. Do we also expect stone-faced toughness at all costs in the face of adversity? We no longer hiss and spit when shin splints disable our favorite lumbering first baseman. Will there come a time when a monthlong stress-induced DL stint isn’t met with indignant scoffing?

Zach Greinke and the Royals may have done something relatively revolutionary, if we ever come to deciding that what they did was a model for success. There will always be decisions to make. We can’t keep paying for your surgeries if you can’t throw a strike to begin with, and maybe Khalil Greene is just not good enough to be paid $6.5 million to undergo counseling. Baseball, at some level, will embrace this. It’s about talented superstars and winning organizations. If the next Tim Lincecum needs a little help understanding how to deal with his situation, why shouldn’t we as fans demand that our training staff gets right on that?

June 26, 2009

Albert Pujols homers off Brad Lidge

Many pencils have been snapped in half, and many cabana shirts ruffled, in the fret-mongering which has accompanied this so-called sabermetrics thing. So, too, have certain statistics become haplessly passe, relegated to the same corners of Americana where rotary telephones and record players elicit warm memories but little actual use.

The RBI is one of those statistics. By now, criticizing the Run Batted In is relatively cliched: it’s a comfortable realization, that RBIs are really a measure of a bunch of things that are totally out of control of the hitter. He can’t account for whether or not the guys in front of him reached base. He can only try to get a hit, and he will only be successful a small fraction of the time at that. He’s not trying harder when there are guys on – or he shouldn’t be, at the very least. A batter will get a hit of some sort based on some ethereal probability function, and if there happen to be other batters occupying bases, they stand a good chance of being knocked in. That’s what RBI tend to measure: a batter, in a very indirect way, through the productivity of those around him.

Still, there are many who tend to think via a more bullheaded sort of logic: if you drive in your teammates, you are by definition being productive, so it’s perfectly reasonable that how many teammates you drive in is equal to how productive you are. This isn’t entirely inaccurate, since good hitters will tend to knock in their teammates more often than bad hitters, but it misses the point. A guy who gets a leadoff double is probably doing more than his teammate who comes along and singles him in, and to measure by individual runs and RBIs is to needlessly obfuscate this fact.

That said, it’s still interesting to look at who’s been knocking guys in, because yes, these players do tend to be among the best in the game. What follows is a list of RBI shares, or the percentage of a team’s total Runs Batted In that a player is responsible for — and the players are, of course, all stars. But the gradations and the rankings are not what you’d logically expect, and it’s interesting to postulate on why, exactly, they end up like they do here. The simple answer is that there happen to be guys on base when they get hits. The more complicated answers? I don’t know. Maybe they’re below. Maybe they’re not. You tell me.

Numbers 1-5:

1. Albert Pujols, St. Louis (70 RBI, 22.01%): Was there ever any doubt in your mind? There is little to write about Albert Pujols, who is the best hitter in the game and could finish his career as one of the best hitters of all time, that hasn’t already been said. His status atop this list is not a testament to his prime spot in a productive lineup, it is a spot he himself has earned alone. Pujols has 70 RBI, which is more than anyone else in baseball, and 32 more than Ryan Ludwick, the team’s second-best run producer. His 26 homers, also the most in baseball, are 15 more than Ludwick has. It’s almost unfair to the Cardinals to point out how much better Pujols is than everyone else in that lineup, because he’s better than anyone else in baseball period, but it’s true. No matter who you think the Cardinals’ second-best hitter this year has been — Ludwick, Rasmus, Schumaker — he hasn’t really been all that good. Pujols is positively scary, and he’s the reason that St. Louis is in first place in the NL Central right now. Even if you think you’re paying attention to him right now, pay more attention. You will not see another like him.

2. Prince Fielder, Milwaukee (68 RBI, 20.36%): Prince Fielder might never again reach the 50-homer plateau, something he did as a big-league sophomore in 2007, but that doesn’t mean he’s getting worse as a player. Still just 25 years old, Fielder is quietly having an excellent season in Milwaukee, batting .301 with 18 homers in 72 games for the Brewers. The svelte 1B is posting a career-best walk rate of almost 17% and looks to be developing a more discerning eye at the plate. Lefties gave him fits last year (.239), but he’s dramatically improved his splits against them. He leads the Majors in Win Probability Added. Fielder has made good on the productivity that has surrounded him all year – guys like Rickie Weeks, Corey Hart, and Ryan Braun. Even Craig Counsell (taking over for Weeks) and Mike Cameron have been decent in their roles. The Brewers bought out his ’09 and ’10 arbitration seasons for a combined total of $18 million, and they got a deal.

3. Jason Bay, Boston (69 RBI, 18.80%): Remember when Jason Bay was no sure thing to be able to handle Boston’s hectic environment? Neither do opposing pitchers. Bay’s timing is impeccable: he’s in line for a career year in 2009, which, in the middle of Boston’s lineup, allows him to rack up all sorts of nifty counting stats (his 69 RBI are second only to Pujols). It’s all the more impressive that Bay didn’t miss a beat when David Ortiz spent most of the season’s first half hitting like Pokey Reese. Bay assumed Top Dog status in Boston’s lineup without blinking, and it’s not the Fenway Effect: his OPS is 100 points higher on the road than it is at home. He’s hitting righties, lefties, and is slugging .703 with runners in scoring position. Ellsbury, Pedroia, Youk, and Lowell have all posted very strong seasons — time and time again, they’ve been on for Bay, and Bay has delivered, helping keep Boston in first place in the East.

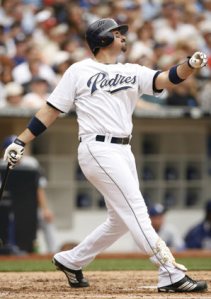

Adrian Gonzalez

e4. Adrian Gonzalez (47 RBI, 17.67%): Adrian Gonzalez is perhaps the most underrated and underappreciated offensive player in baseball. His .275/.417/.599 line is impressive enough before you consider that it’s been protected by Chase Headley and Kevin Kouzmanoff, who while combined have hit 17 homers on the year, they are also batting just .236 and striking out in 25% of their at-bats. Gonzalez is also posting just a .256 Batting Average on Balls in Play, though that may be partially deflated by the fact that 24 of his hits have never technically entered the field of play. Those 24 homers are second to only Albert Pujols, and Gonzalez plays half his games at Petco, the Majors’ toughest park to hit homers in (16 road HR, 8 home HR). David Eckstein, who hits before him, has a .329 OBP, and that’s not even the worst they did to AG. Through the end of May, the Padres inexplicably led off with either Brian Giles or Jody Gerut, neither of whom could manage to get on base at even a .300 clip. They’ve plugged Tony Gwynn Junior into the leadoff hole in June, and he’s responded by posting a .420 OBP; getting some runners on base in front of Gonzalez will help recover at least some small amount of his incredible value, which is mostly wasted on this woeful ballclub. He has the fewest RBI (47) on this list, but it’s not for lack of trying; he is simply not deriving any value from his spot in the lineup. Oh, and he’s making just $3 million this year. Think the Marlins — who traded him away as a minor leaguer in ’03 for Ugueth Urbina — would like a do-over?

5. Mark Reynolds (53 RBI, 17.49%): Mark Reynolds strikes out a lot. A whole lot. In 2008, he became the only player in Major League history to strike out 200 times in a season. Think about that. He’s the only person to have ever done that in history. He’s locking horns with Chris Davis (TEX) for the rights to break that record again this year. It’s as much a part of his identity as is the fact that he is from Kentucky and plays the field with shoes made of bricks. So severe are the shortcomings in his game that he would probably not even be in the Majors were it not for the fact that he is also preternaturally inclined to hit ludicrous, prodigious home runs when he squares up the baseball. Reynolds average Standard Distance for his home runs (or the distance the ball would travel from plate to ground in a neutral environment) is 415 feet, tying him with Ryan Howard for 8th-farthest in the Majors. His 21 homers are matched by a .269 batting average, which for Reynolds is almost comically high and will certainly not persist. Only the aforementioned Chris Davis swings and misses more often than him, and Davis is batting .209 with just 6 fewer homers. He’s hitting just .247 with RISP and 9 of his homers have come with the bases empty, so his production has simply been extremely consistent.

Numbers 6-10:

6. Justin Morneau (58 RBI, 17.37%): Your 2006 AL MVP would be joined on this list by the slick-hitting Joe Mauer (.395/.465/.697) but for Mauer’s lack of April plate appearances. Morneau and Mauer have been a prodigious pair at the heart of the Minnesota lineup, which has been quietly productive, rounded out by strong years from Michael Cuddyer and Denard Span, who has taken over leadoff duties for the Twins and posted a .388 OBP.

7. Brandon Phillips (48 RBI, 16.78%): After years of striking out twice as much as he walked, Phillips, the game’s model late bloomer, has finally begun to reverse the trend. His K/BB is an even 1.00 in 2009; Cincinatti’s offense is not very good, but Phillips’ approach has allowed him to be successful in spite of the unimpressive cogs surrounding him as of late.

8. Adam Dunn (50 RBI, 16.61%): Adam Dunn waited a very long time to get a deal this past offseason, and he finally went where the biggest dollop of cash was: $20 million for two years in a Washington Natinals uniform. The pitching’s been much more embarrassing; Dunn at least has Ryan Zimmerman down there, and Nick Johnson has quietly been quite good in the time he’s played. A sixth straight 40+ HR season is very much in reach, especially if he starts hitting at home (.774 OPS).

9. Raul Ibanez (59 RBI, 16.53%): He has either been talked about too much or too little this year; the Phillies were roundly criticized for jumping the gun and giving the aging Ibanez a three-year deal, but they smelled blood in the water. For $6.5m in 2009, he’s been a revelation in that lineup, helping pace the Phils as they try to get back to the World Series. He hasn’t even been in a typical “prime” RBI spot, spending most of his time at #6 while Ryan Howard (#11 on this list) bats cleanup.

Torii Hunter: Production Nothing New

10. Torii Hunter (54 RBI, 16.36%): Torii Hunter has spent most of the first half hitting cleanup for the Angels in Vlad’s absence, and did not disappoint. The 13-year veteran posted a .915 OPS as the #4 batter, and has shifted to #3 now that Vlad is returned. He’ll continue to produce with the bat — and the glove — the way he always has, and perhaps always will.

Numbers 11-20:

11. Ryan Howard (57 RBI, 15.97%)

12. Jose Lopez (42 RBI, 15.73%)

13. Bengie Molina (41 RBI, 15.65%)

14. Carlos Lee (43 RBI, 15.47%)

15. Paul Konerko (46 RBI, 15.38%)

16. Evan Longoria (61 RBI, 15.29%)

17. Ryan Braun (51 RBI, 15.27%)

18. Mark Teixeira (57 RBI, 15.16%)

19. Lance Berkman (42 RBI, 15.11%)

20. Aubrey Huff (47 RBI, 15.06%)

April 7, 2009

Rounding Out the Rotation

Posted by Finn under Lifetime Achievements, Recent Developments | Tags: Chicago White Sox, Kansas City Royals, Minnesota Twins, Seattle Mariners |1 Comment

Great baseball players are extremely hard to come by.

There may come a time, many years in the future, when the sporting world is seized by a feverishly unscrupulous zeitgeist of genetic manipulation, an era in which human beings have been pushed to the limits of their physical structures and contests become breakneck battles of endurance between hyper-athletic specimens of biological and chemical engineering. This is the sort of thing that’s occasionally dramatized in bad science fiction movies: in the year 2050, athletes are less a gifted portion of humanity and more a subspecies unto themselves. A wide receiver with a 13-foot verticals artfully backflips over a free safety. Power forwards perform 1080 reverse dunks that shatter the very basketball in their hands into trillions of little sparkling nanoparticles. A square-jawed DH turns on a 130-MPH fastball and sends it screaming toward the right-field bleachers — alas, it is robbed by the center fielder, who scrambles up a twenty-foot wall to make the catch.

That time, thankfully, is not now. In fact, we like to tell ourselves that it is quite the opposite: now that we’re paying such hawkish attention to the big anabolic meanies, the artisans of old-world skills such as – gasp – defense are suddenly hot properties. It is, ostensibly, how the Rays were able to be so successful last year, and how teams like the Mariners – who will start an outfield of Endy Chavez, Franklin Gutierrez, and Ichiro Suzuki – are earning pre-season hype as the this year’s surprise sleepers. A run saved, as they say, is just as good as a run earned (and currently costs a lot less).

That time, thankfully, is not now. In fact, we like to tell ourselves that it is quite the opposite: now that we’re paying such hawkish attention to the big anabolic meanies, the artisans of old-world skills such as – gasp – defense are suddenly hot properties. It is, ostensibly, how the Rays were able to be so successful last year, and how teams like the Mariners – who will start an outfield of Endy Chavez, Franklin Gutierrez, and Ichiro Suzuki – are earning pre-season hype as the this year’s surprise sleepers. A run saved, as they say, is just as good as a run earned (and currently costs a lot less).

Of course, there are still the freaks of nature that make fans’ hearts flutter, the shining temples of accomplishment within the game whose faces get put on video game boxes and sell us disposable razors. And as most sensible observers of the game will tell you, the sport is not clean, and never will be, because fans’ dollars go toward watching the best players, not watching the best drug testers. But most teams have only a handful of notoriously skilled players. Pick a team at random – say, the Minnesota Twins – and you’ll be able to count the stars on one hand. Joe Mauer, a hometown kid who’s a skilled offensive catcher; Justin Morneau, a perennial All-Star at first; Joe Nathan, one of the game’s elite closers. Francisco Liriano might get there one day. So might Delmon Young.

But who are these other guys? Many more still, while not superstars, are above-average. Carlos Gomez is very fast and a great defender. Scott Baker is a capable middle-of-the-rotation starter. Kevin Slowey never walks anybody. Their talent, too, comes at a premium, and while they will not make headlines, they will please fans for as long as they keep their heads above the water and avoid really murdering their teams’ chances via whatever holes in their game have prevented them from reaching the upper-echelon. These guys can’t be great, because there isn’t enough greatness left to go around.

Now, the game of baseball is not wont to do any favors: beneath these two layers of ability there lies a massive, churning lake of marginally-skilled players waiting to bubble and froth through and chinks that may appear in the armor of a ballclub as the season wears on. These are not those young prospects whose fortunes appear written in the stars; rather, these are the sedentary beings past which those wunderkinds slide on their way to brighter things.

They are filler.

Sure, they were once young hotshots, the greatest things to ever pass through their high schools and junior colleges. Somewhere along the way, though, the hands of fate brushed them aside. They are occasionally stories of self-ruin (drug abuse, attitude problems) and are occasionally felled by physical malady (see: Mark Prior). More often that not, though, they’re just not good enough at any part of the game. Their reaction time is 0.1 seconds too slow, their fastball just a few miles-per-hour south of acceptable.

Baseball, much like life itself, exposes them with varying levels of haste. Occasionally, these fraudulent icons are able to skip and bounce their way to decent-enough numbers that the men in charge, anxious as they are to get while the getting’s good, reward them with extremely lucrative contracts. Gary Matthews Junior, having flashed 20/20 potential as a young outfielder in Texas, appeared to turn a corner in 2006 when he batted .313 with 19 homers. He was rewarded with a $55 million dollar contract with the Los Angeles Angels, and in 2009 finds himself FIFTH on the Angels’ depth chart, having swiftly proven himself wholly undeserving of the money he was given.

Others still are stuck in a sort of limbo, and can get by for years – maybe an entire career – on a mixture of luck and anonymity. This can happen for a variety of reasons.

Some have excellent skills but have displayed a pathological inability to harness those skills. Daniel Cabrera, a 6’9″ flamethrower from the Dominican Republic, has a fastball that often clocks in the mid-to-upper 90s. He also walks in the neighborhood of five batters per nine innings, and in 146 career starts has a 5.05 ERA. Players like Cabrera carom around the league for far longer than their peers who generate the same results because there are no shortage of men arrogant enough to dream that they can make a tweak here, an adjustment there, and voila: out from the thorny bramble bursts some rare and special player.

For many of these players, that quixotic and ethereal ability is far less apparent. In 1997, the Atlanta Braves selected Horacio Ramirez, the son of two Mexican emigrants, in the fifth round of the amateur draft out of Inglewood High School in California. A better fate could not befall a young pitcher: the Braves were establishing a stranglehold on the National League East, and boasted some of the best pitchers in baseball, three of whom – John Smoltz, Tom Glavine, and Mark Wohlers – were home-grown products. They had a reputation for developing elite pitching, and were an excellent ballclub in a major media market.

Ramirez broke camp with the Braves in 2003 and would go on to make 29 starts for the ballclub, going 12-4 with a 4.00 ERA. Had he registered a few more outs, that of course becomes 3.99; a 23-year old left-hander going 12-4 with a 3.99 ERA in his rookie season is the sort of thing that’s going to inspire  some positive thoughts around the league. So he essentially did that, but unfortunately for him (and the Braves), this was mostly smoke and mirrors. In 182.1 IP, he only managed a woeful 100 strikeouts, walking 72 in the process. He induced a lot of ground balls, though, and in that way was able to limit damage.

some positive thoughts around the league. So he essentially did that, but unfortunately for him (and the Braves), this was mostly smoke and mirrors. In 182.1 IP, he only managed a woeful 100 strikeouts, walking 72 in the process. He induced a lot of ground balls, though, and in that way was able to limit damage.

The next few years revealed two things about Ramirez: not only was he not very good, but he also had serious problems staying healthy. He missed almost the entire 2004 season with shoulder tendinitis, and missed large portions of 2006 with hamstring and finger issues (he also missed a start after being drilled in the head by a Lance Berkman line drive). When he was on the field, he displayed an almost preternatural inability to miss bats. Nestled in between his ’04 and ’06 seasons was a 202-inning 2005; his fastball was clocked a hair shy of 89 mph, and he managed just 80 strikeouts for a 3.56 K/9 figure that was the second-worst in the league, behind only the immortal Carlos Silva (3.39). Silva, to his credit, walked almost no one: his 0.43 BB/9 was far and away the best in baseball. Ramirez walked six times that many batters, making his skillset uniquely unfit for major league service.

By the end of 2006, the Braves had likely soured on Ramirez, and so it was something of a coup for them when the Mariners offered to trade them hard-throwing setup man Rafael Soriano in exchange for Ramirez. The deal was an unpopular one; Soriano was a high-risk brilliant arm and Ramirez was a high-risk mediocre arm. The M’s gave him $2.65 million to avoid arbitration, and in exchange, Ramirez shed the exoskeleton of fortuitousness that had allowed him to hang on in Atlanta for so long. He started 20 games which somehow added up to just 98 IP, walked more (42) than he struck out (40), and posted a very impressive 7.16 ERA, all while missing a month and a half with shoulder problems.

That was the highest ERA in the major leagues among pitcher who threw at least 90 innings. A 7.00 ERA is a little bit like a 20-loss season. When a starter loses 20 games, it is a painful badge of honor: for most pitcher, the team will stop the bleeding around 15 losses or so, and just run someone else, anyone else, out to the mound. If a starter reach 20 and his team is still starting him, it’s probably because they have faith that the experience will further hone a future starter’s craft. A 7.00 ERA is just as unusual, and though a pitchers ERA is more indicative of his skill than his Win-Loss record, maybe a guy’s just getting unlucky, or is leaving an excellent fastball up in the zone.

The Mariners had no real reason to believe that Ramirez was destined for the slightest bit of stardom. He was a groundballer with unacceptably poor control and weak stuff. Inexplicably, the Mariners offered him a raise for 2008, handing him $2.75 million instead of going to arbitration.

This is the sort of thing that makes a tale exceptional and unusual. Poor talent is poor talent, and there is an endless supply of it. It’s the teams that tend to mold them into goats, martyrs, and losers.

The Mariners, realizing the foolishness of their offer to Ramirez, released him less than two months later; the team ended up on the hook for about $500,000 of the deal. He floated around the talent pool until late April, when the Royals scooped him up, signed him to a minor league deal, and converted him to a reliever.

He did mostly mopup work for the squad, and the results looked good enough to interest the White Sox, who acquired him in August for a speedy Brazilian outfielder named Paulo Orlando. Orlando is certainly Brazilian and he is very much an excellent runner, but it is something of a mistake to call him an outfielder (1383 AB, 78SB, 67BB). Ramirez too was miscast in his own right: the White Sox attempted to use him as a left-handed specialist, but he wasn’t very good at it. In truth, Ramirez hadn’t been terribly good against lefties since he was new to the league, and being that he wasn’t very good against righties either, the White Sox determined that they probably would not require his services beyond 2008 and let him walk.

He only had to wait a few months for a job opportunity: last December, the Royals came to him and offered him $1.8 million to rejoin the ballclub for the 2009 season. This time, though, they made it clear that they intended to have  him compete for a spot in the rotation, and when spring training began, they slotted him in as a starter. He absolutely was mauled all spring training long, surrendering 25 earned runs in 25 innings and looking every bit the overmatched pitcher that he’s been since his rookie year.

him compete for a spot in the rotation, and when spring training began, they slotted him in as a starter. He absolutely was mauled all spring training long, surrendering 25 earned runs in 25 innings and looking every bit the overmatched pitcher that he’s been since his rookie year.

While it is true that spring training performances are basically meaningless, it’s fine to make the assumption that if a player who has always stunk stinks again in spring training, he will continue to stink into the regular season, and probably for the rest of his life. He’s scheduled to start against the New York Yankees this Saturday.

So what gives? Is an out-of-shape washed-up 29-year-old left-hander with a history of injury issues and control problems that can’t strike anyone out really the best the Royals can do with that slot in their rotation? Their next options would appear to be Luke Hochevar and Brian Bannister.

Hochevar was the Royals’ first pick in the 2006 draft; in fact, they selected him first overall, taking him ahead of Brandon Morrow, Clayton Kershaw, Tim Lincecum, Max Scherzer, and Joba Chamberlain, amongst others. This would’ve been bad enough were it not for the fact that in the previous years’ draft, Hochevar was the subject of great controversy when he, after being drafted by the Dodgers, dumped his agent (Scott Boras), took the Dogers’ $3 million signing bonus, and then went back to Boras the next day and canceled the agreement. Hochevar spent the remainder of the year playing Independent League ball, then re-entered the draft in ’06. He made 22 starts with the Royals last year, and while he is destined to be something of a disappointment, he was not all that terrible, with a 72/47 K/BB ratio in 129 IP. That’s too many walks, but it was his first full season, and he allowed less than a homer per game. His 5.51 ERA was a little bit unlucky, as his strand rate (62%) was second-worst in the league (min: 120IP).

Brian Bannister is a better story than a pitcher: he was a walk-on second baseman at USC, converted to a pitcher, and had a very successful college career. He is also a devout Christian, a member of Lambda Chi Alpha, is an avid photographer, and holds a special place in the hearts of sabermetricians everywhere for openly studying baseball statistics. To summarize, Brian Bannister is a very smart guy, extraordinarily smart for a baseball player; he realizes that he’s not a great pitcher, and so he’s looking for an extra edge in numbers where others might find them in pill bottles or rabbits’ feet. The “not a great pitcher” part is more important for the Royals that the intelligence factor, though in handing Horacio Ramirez a rotation spot – to say nothing of Sidney Ponson – the Royals have indicated that they need brains just as desperately as they need bats and arms.

Hochevar should almost certainly be starting over Ramirez. Instead, both he and Bannister will begin the year in AAA, while the Royals’ top minor league pitchers – Daniel Cortes, Tim Melville, Danny Gutierrez – pitch in A and AA leagues, waiting for 2010 or 2011 debuts. The Royals’ system is in an awkward place right now: they have top young talent at the major league level in Zach Greinke, Alex Gordon, and Joakim Soria, and have a decent amount of projectable prospects, but those guys are years away.

Positions like these dictate that the front office bridge the gap and do some real work to keep the team competitive while young talent matures and gets the fans excited. This is especially true for the Royals, who play in the worst division in baseball. They could finish third in the division with a .500 record, which is something of an accomplishment when your team hasn’t been to the postseason in 23 years and has a .416 winning percentage this decade. Sure, the team could pony up for Pedro Martinez, but they’re a low-payroll club and already have most of their ill-advised pitching contracts locked up in the bullpen (Kyle Farnsworth and Ron Mahay will earn $8.25m in 2009). The team is also paying Ross Gload $1.5m to play for the Marlins.

Horacio Ramirez is an awful pitcher, but he didn’t sign himself to that contract. The Royals’ decision to put Ramirez in the starting rotation is basically indefensible, and it is unclear how exactly he will improve upon what Luke Hochevar could’ve done. Career 39-33 record, 4.59 ERA. Horacio Ramirez is what’s considered “freely-available talent” at best, which is unfortunate for the Royals, being that they are paying him almost two million dollars for his services when they’re already paying a number of guys in AAA who could’ve done the exact same thing as him.

What is it exactly that causes teams to make these sorts of decisions, to hand over $2m and a roster spot to a player who offers them absolutely nothing? What fundamental, hard-wrought biases muster up these tragic, old-timey missteps? Is the team so desperate for a left-handed option in the rotation that they are willing to eschew rationality in their pursuit of one?

There are countless biases which skew the direction of human decisionmaking, leading even normally reasonable people astray into the tar pits from which players like Ramirez are dredged. Perhaps even more remarkable is that the Royals’ other options are so bland as to make proper the criticism of their spending habits rather than their level of talent at the Major League level. Good baseball players are extremely hard to come by; the Royals don’t have enough of them to matter this season, and they’ve complicated matters by thinking that they need to pay a premium for a starter who’ll strike out fewer batters this season than their closer.

It’s a tough league. Talent is at a premium, and organizations are constantly at war over it; each team must figure out how to retain their young stars for long enough to be able to, with help from a supporting cast of free agent signees and trade acquisitions, make a run at the postseason and the financial windfalls which generally accompany such berths. Dollars are more precious than ever these days, which makes younger, cheaper players absolutely critical to an organization’s success. No team can draft and develop a 25-player Major League roster, so, and Free Agency will never be passe. With smart spending habits and a shrewd baseball mind, there are just enough guys out there to make it work.

For everyone else, there’s Horacio Ramirez.

February 12, 2009

Your Outrage is Wildly Ignorant

Posted by Finn under Recent Developments | Tags: New York Yankees |[2] Comments

“When it got to the editorial stage everyone knew the cards were down. What followed was as carefully produced as a ballet. The police got ready, the gambling houses got ready, and the papers set up congratulatory editorials in advance. Then came the raid, deliberate and sure. Twenty or more Chinese, imported from Pajaro, a few bums, six or eight drummers, who, being strangers, were not warned, fell into the police net, were booked, jailed, and in the morning fined and released. The town relaxed it its new spotlessness and the houses lost only one night of business plus the fines. It is one of the triumphs of the human that he can know a thing and still not believe it.”

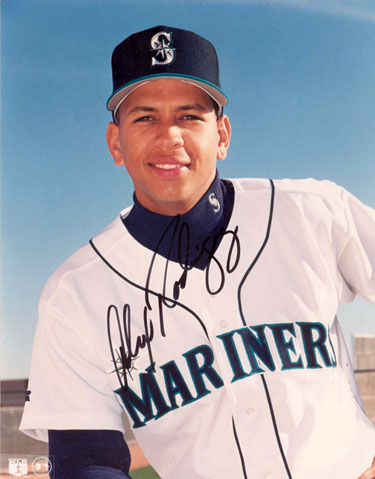

— John Steinbeck, East of Eden

In breaking the revelation that Alex Rodriguez, perhaps the biggest name in Major League Baseball, failed a random, league-mandated PED test in 2003, Selena Roberts and Sports Illustrated have unleashed a maelstrom of hatred and condemnation throughout the sporting world, most of it toward the hitter himself. Thanks to the report, we have now what appears to be a clear timeline, and can use it to track the death of modern baseball from catalyst to ashes. Alex Rodriguez, a young superstar in his prime, took illicit substances to help himself get an additional edge over the competition. He was tested for it in 2003, and test results came back positive. He said nothing, admitted nothing while the fervor grew over Performance Enhancing Drug use in Major League Baseball, and went so far as to lie on national television about ever having used them. It was leaked in 2009 that he’d used, and after a couple days, he admitted to a television audience that he had in fact used them, but that was in the past, and he was sorry.

ENTER: Outrage.

Fans have been struck by this news as a child is struck when he is told that not only is Santa Clause fake, but that the man they thought was Santa Clause was actually a whitewashed Afghani who implanted a large bomb in their ear that is going to detonate on their 18th birthday. For sportswriters and pop culture critics, this is the filet mignonof stories, the easiest of moral pulpits to climb upon and proselytize. Emotions range from shock to anger to disappointment. Seething viewers yearn to tear the accused apart, limb-from-limb, until they have rid the sport’s gene pool of the kind of nefarious selfishness that surely courses through the testosterone-inflated bodies of the Dark Era’s exaggerated sluggers. This is a sad, misguided, and altogether unintelligent quest for culpability. No grand individual failures by any specific players have occurred here. What we have is a failure of a professional sporting organization, of union leadership, and of a national body of fans in general. It is a lesson in mass incompetence, and the furor of a nation is providing an unwitting yet altogether perfect crescendo.

Fans have been struck by this news as a child is struck when he is told that not only is Santa Clause fake, but that the man they thought was Santa Clause was actually a whitewashed Afghani who implanted a large bomb in their ear that is going to detonate on their 18th birthday. For sportswriters and pop culture critics, this is the filet mignonof stories, the easiest of moral pulpits to climb upon and proselytize. Emotions range from shock to anger to disappointment. Seething viewers yearn to tear the accused apart, limb-from-limb, until they have rid the sport’s gene pool of the kind of nefarious selfishness that surely courses through the testosterone-inflated bodies of the Dark Era’s exaggerated sluggers. This is a sad, misguided, and altogether unintelligent quest for culpability. No grand individual failures by any specific players have occurred here. What we have is a failure of a professional sporting organization, of union leadership, and of a national body of fans in general. It is a lesson in mass incompetence, and the furor of a nation is providing an unwitting yet altogether perfect crescendo.

This is not about absolving PED users of any and all wrongdoing, about turning a blind eye to the indiscretions of an era. Not is it about being jaded, about simply believing that everyone in sports is an evil cheater and we’re wasting our time and energy even caring about them because the sport is lost forever. It is about the human process of learning from past mistakes, and about getting to the core of those mistakes. Growth is most purely achieved when it arises from struggle, but this cannot be the case if we, as a society, simply grab the low-hanging fruit and grind it into the concrete with the weight of our collective knee-jerking. The A-Rod story is essentially the final straw; the last shred of deniability has been removed, and we must now seriously accept that PEDs penetrated all levels of the game at least during those years, and that we will never truly know what effects they had. We have been forced into action, and what has the reaction been? We have quickly coalesced into an unthinking mob of witch-hunters. There is strikingly little desire to move beyond the incendiary and to begin to address the problem in any meaningful way. Where is the national outrage over the incomprehensible failures of Bud Selig, Donald Fehr, Gene Orza, and of management and the press? Are we so oblivious that we content ourselves with the widescale reality that all we really want to do is eviscerate our fated celebrities?

This simply isn’t about A-Rod. It isn’t even about Selena Roberts, who just happens to be writing a book on A-Rod, to be released this May by HarperCollins and whose sales figures will undoubtedly be receiving a massive boost by Roberts’ story in Sport Illustrated. It’ll be the second major book this year to implicitly profit from trashing the third baseman: “The Yankee Years” by Joe Torre (and Tom Verducci, another SI writer), made headlines when anecdotes were leaked about Rodriguez being referred to as “A-Fraud” in the Yankee clubhouse. The role that “journalists” play is important here, but not necessarily on an individual level. There’s obviously nothing wrong with what Roberts did in this case. She did what any other journalist would do – when handed an irresistible story, she saw it through and delivered it to the world. Though she is writing a book on the player, her work on it began prior to this most recent controversy, and to her credit she has not taken to ESPN and NBC to cast Rodriguez as an unscrupulous monster. She simply got the angle and broke the story, and no one could’ve rightfully asked her not to do so.

The issue of player PED use is much larger than can or should be confined to Rodriguez, but as a player who is as “big” as anyone else in the game, he is an appropriate lens, and it is now fitting that we examine the problem through him. People are angry that he used steroids, and angry that he lied about it when asked. Beyond that, the fans don’t much care – who cares about why he did it, and who cares about mistakes others might have made? Alex Rodriguez took steroids and, though it took a while, got caught. Case closed. So what if this information never should have come to light? Better that it did, because there should be no sanctuary for the damned in this world or any other. But is it enough to simply behead our former idols and let them stand as grim examples to future players who might dally on the dark side? Or do we care about avoiding future blemishes as best we can, and in the process, can we ask tough questions of ourselves and our contemporaries within and outside of the game? Forget about the baseball players, most of whom are morons anyways. How did your favorite writer down at the Post contribute to this situation? How did the smart white guys in suits – the GMs, the MLBPA, the MLB front offices – play into this disgrace? How did you make a mess of this, and do you come seeking redemption or revenge?

Alex Rodriguez took steroids, lied about it, and then claimed he didn’t even really know what he took, but that yeah, it was something he shouldn’t have. Why is he not the festering core of the issue?

Let’s discuss the claim that he didn’t know exactly what Performance Enhancers he used back in Texas. Is this likely? There exists the widespread belief that if you are paid for your physical fitness, as an athlete basically is, it is incomprehensible that you would not hawkishly account for everything you ever did that might impact that fitness in some way. To think this way is to hold the human being behind the player to a different set of standards and expectations that you hold other humans to. Any person will take the time to do a certain thing when and only when it is beneficial for him to do that thing above all other things. There are two economic principles at play here – opportunity cost and rational ignorance.

Let’s discuss the claim that he didn’t know exactly what Performance Enhancers he used back in Texas. Is this likely? There exists the widespread belief that if you are paid for your physical fitness, as an athlete basically is, it is incomprehensible that you would not hawkishly account for everything you ever did that might impact that fitness in some way. To think this way is to hold the human being behind the player to a different set of standards and expectations that you hold other humans to. Any person will take the time to do a certain thing when and only when it is beneficial for him to do that thing above all other things. There are two economic principles at play here – opportunity cost and rational ignorance.

The pursuit of information has a cost, that cost being the loss of whatever else you could’ve been doing in the time it took you to obtain that information. For any athlete, the opportunity cost of rigorously screening their nutritional supplements is equal to the value of the alternative. The alternative value for any athlete is always very high – you could be doing other things, like practicing and playing and performing at the highest level possible (the value of this is millions of dollars), or getting away from the pressure of the game and relaxing to keep your sanity (or womanizing, gambling, whatever – to each his own). What is the cost of not knowing what gets put into your body? Back in the midst of “The Steroid Era,” it was almost zero. There were very few possible repercussions for those guys, and if you did not have much of a psychic cost(i.e. it didn’t make you feel guilty), the benefits of ignorance far outweighed the cost. Those costs could even be frayed by the subconscious allure of plausible deniability. The details were out of sight and out of mind for these guys. Their ignorance on the subject was rational, as it is irrational to pursue ends that do not justify the means. It’s frequently cited, for example, as one of the chief reasons that people don’t educate themselves about political issues: the cost of doing so generally outweighs the benefits. Does your life really change at all if you bother to spend your free time getting off the couch and becoming a proponent of some referendum on putting slot machines at gas stations?

It’s not just athletes that do this, even where diet and nutrition are concerned. The consumer Dietary Supplement Industry is a behemoth, and growing every day. Sales in the U.S. alone reached about $22.5 billion last year. While the overwhelmed FDA continues to slowly implement new regulations on producers, the fact remains that said supplements don’t even need FDA approval to be sold in stores. You could literally create one yourself, made of sugar and powderized lawn clippings, and sell it tomorrow. Millions of Americans take these supplements every day to encourage weight loss, muscle gain, improved focus and vitality — the list of reported benefits goes on. How many of these (legal) users could tell you exactly what they were taking? 1%? 0.1%? Beyond the brand name and advertised effects on the box, can, or bottle, most people are clueless as to what’s going into their body or what the stuff’s actually doing once it gets in there. So why should star athletes – who are insulated from responsibility for their entire adult lives – be any different? Not only would they not know exactly what was going into their body, but they don’t even have a brand name to reference. What they do have is an experienced, highly-regarded professional trainer, used by other stars in the game, telling them “this is the stuff you need.” You’re a ballplayer. Maybe you haven’t taken a science course since high school geology – what the hell do you need to know about chemistry? You’ve got the industry best watching out for you, and besides, you have enough pressure on you just worrying about performing for the fans. A consumer assumes that if a product is sold to them at GNC, it’s safe and legal. The assumptions made by both parties are just the same.

If you lead a extremely high-pressure life and your boss hired a professional to wipe your ass for you every morning, how long before you stop paying attention to what brand of toilet paper the guy was using?

A-Rod’s image problem in this case is compounded by the fact that last winter, in an interview with Katie Couric, he explicitly claimed to have never used steroids. Fans now know that this was not only a lie, but a gratingly arrogant one: he’d never used PEDs, he claimed, because he was too good to need them. At the heart of the matter is the lie, not the arrogance, and again, the lie was a rational act. The most important consideration to make here is that the testing was supposedly anonymous, and that the players would have assumed that to be true. It wasn’t just the Union that promised the information to the players, it was Major League Baseball itself via the 2003 Collective Bargaining Agreement. Here’s the relevant portion of the 2003 CBA that dealt with sample collection procedures:

All Collectors must adhere to the following collection procedures:

1. The Collector, who will be male, will be provided with a master list of all Players to be tested, along with an identifying number. The Player will provide photo identification to the Collector. If the Player does not have photo ID, Collector will indicate this on the Group Collection Log and have a Club representative (e.g., a trainer, or coach) positively identify Player.

2. After identification, if the collection is for Survey Testing, the Collector will invite the Player to affix the assigned identifying number to the specimen vial. Prior to observing the Player provide the urine specimen, the Collector will explain to the Player why the number is being affixed, as follows:

(i) The test is being taken as part of a survey only, and is without any disciplinary consequences;

(ii) The survey requires two tests of the same Player, in order to rule out positives attributable to legal nutritional substances only, and this is the first of those two tests; the second will be administered in 5 to 7 days;

(iii) The collector must tell the donor the following: “You must refrain from taking any nutritional supplements until after the second test is conducted”;

(iv) At the conclusion of any Survey Test, and after the results of all tests have been calculated, all test results, including any identifying characteristics, will be destroyed in a process jointly supervised by the Office of the Commissioner and the Association.

That last section is obviously the critical one: after the results have been calculated, all identifying characteristics will be destroyed. When were those results calculated? Way back in 2003, when the league announced that PED use in baseball was high enough for mandatory testing to kick in during the 2004 season (5-7% of samples tested positive). If you’re paying attention, you’ll notice that the supposedly “anonymous” testing was not at all anonymous by design: each player was given an ID number, and the ID number was recorded along with the sample, creating a very easy and traceable path from sample to player. Even if you’re not smart enough to notice this – and there’s no reason to think this would’ve ever worried someone like A-Rod – you have been assured that all the evidence has been destroyed. By the time of the Couric interview, the test samples were more than four years beyond the date when they should have been trashed. If anyone could’ve known that A-Rod tested positive, they’d presumably have known well before the Couric interview.

Also important is 2.i, which states that a positive test has no disciplinary consequences. Rodriguez knew that he’d tested positive, but also knew that per the CBA, he could not be disciplined by Major League Baseball for doing so. Only in the court of public opinion could he be held accountable for his past discretions, and so he did what any human being would do in his situation: he lied. He lied because he had the implicit backing of Bud Selig and Donald Fehr and Gene Orza to do just that. Had he told the truth, he would have been punishing himself for something that not even MLB or the MLBPA saw fit to punish him for. He would have been sacrificing his own career and, because he was perhaps the league’s best player, the careers of any and all of his contemporaries. He knew that to indict himself was to indict the era, to open the floodgates to the shadow of doubt that would irreversibly entrench itself over every single person to ever don a uniform during those years. And for what? Ethics? A clean conscience? Why would he care about those things? He is a self-absorbed star, and while that may be annoying, there is nothing unethical or illegal about it. For being himself and doing what he does, grown men are willing to make him a financial god amongst men (by the time his career his over, his career salary will likely total over $450 million). Jeopardizing that wouldn’t have been honest. It would have been insane.

Also important is 2.i, which states that a positive test has no disciplinary consequences. Rodriguez knew that he’d tested positive, but also knew that per the CBA, he could not be disciplined by Major League Baseball for doing so. Only in the court of public opinion could he be held accountable for his past discretions, and so he did what any human being would do in his situation: he lied. He lied because he had the implicit backing of Bud Selig and Donald Fehr and Gene Orza to do just that. Had he told the truth, he would have been punishing himself for something that not even MLB or the MLBPA saw fit to punish him for. He would have been sacrificing his own career and, because he was perhaps the league’s best player, the careers of any and all of his contemporaries. He knew that to indict himself was to indict the era, to open the floodgates to the shadow of doubt that would irreversibly entrench itself over every single person to ever don a uniform during those years. And for what? Ethics? A clean conscience? Why would he care about those things? He is a self-absorbed star, and while that may be annoying, there is nothing unethical or illegal about it. For being himself and doing what he does, grown men are willing to make him a financial god amongst men (by the time his career his over, his career salary will likely total over $450 million). Jeopardizing that wouldn’t have been honest. It would have been insane.

Since the first time men were paid to compete athletically against other men, the message has been the same: go win. Above all else, this is the manifesto of the elite physical competitor. Win. When in doubt, do what it takes to win. The doubt, of course, is a moving target. Seldom are cases so extreme as you’ll find in say, The Last Boy Scout, when a wide receiver is so affected by a gambler’s threats that he shoots three defenders in the middle of a game. The truth of the matter is that when a young Alex Rodriguez partook in PEDs, there was almost no doubt to speak of. Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa were American heroes, and though you couldn’t just come out and admit your usage after the androstenedione story, without probable cause, no player could even have been tested for PEDs. The coverage given to steroids was so fringe and lackadaisical, and the rewards for performance so massive, that it was only “morals” (or concerns about your balls shrinking) that would have prevented any player from using, and for international fame and $25 million a year, you’ll find an endless list of volunteers who’ll accept just about side effect you can throw at them. Can you really argue that professional baseball players ought to be leaders in professional ethics?

Where was the outrage in 1998, when Steve Wilstein spotted the andro in McGwire’s locker? Shouldn’t that have sealed it right there? It took five years for baseball to even start testing, and ten years for most fans to care. How is it that a reporter could obtain leaked information from a supposedly anonymous test administered a half-decade ago to break a story, yet no one could break this story when PED use was actually at its peak? The people who get paid to poke around clubhouses and asks endless questions of players and managers didn’t notice something that they now decry as a massive bacchanalia of immorality? No one could break the story because no one cared. Retroactive outrage is amongst the most stupid of moral ventures, but if enough red-faced reporters froth over the past, people will pay attention to the histrionics, and suddenly history is rewritten. The players weren’t fighting to get a freely-available edge; they were corrupting the country, urinating on the American Flag, lying to the children. They were stealing fans’ hard-earned money, their honestly-earned money, and selling them a fake product while trampling on the honest records of the past. If you’re not sure about an average baseball player’s level of intelligence and moral sophistication, go read Ball Four. Can you actually expect those same individuals to have done any different than they did?