In the summer of 1992, the Oakland Athletics used their second pick in the amateur draft to select Jason Giambi, a bright-eyed third baseman out of Long Beach State who’d hit .407 in his sophomore season and won back-to-back all-league first-team honors after being tabbed as the Big West freshman of the year in 1990. The A’s assigned him to low-A Southern Oregon; by 1994, he was playing third base for the Tacoma Tigers of the AAA Pacific Coast League. His team-best .978 OPS (AAA Edmonton Trappers) in 1995 earned the stud prospect a mid-season callup; he walked and singled in five trips to the plate in his first game, and hit his first major league homer against David Cone later that summer. By 1996, Giambi had earned himself a starting gig, though he didn’t necessarily have a position, splitting time between 3B (Scott Brosius), 1B (Mark McGwire), and LF (Phil Plantier). He appeared in 140 games and managed to hit 20 homers while posting an OPS+ of 109. Plantier, whom the A’s had traded for prior to the ’96 season, finished the year at .212/.304/.346. Smartly, the team let him walk that fall and handed over the left fielder job to the 26-year-old Giambi. He wasn’t a very good outfielder, though, so when the team gave Mark McGwire away to the St. Louis Cardinals, they shifted Giambi to first base and he stuck there. He re-upped with the A’s after the 1998 season, signing a three-year, $9.3 million contract to keep him in town through 2001.

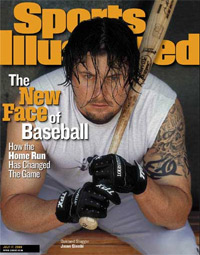

Giambi homered in his first at-bat of the 2000 season, a deep blast to right field off of Hideo Nomo, and then hit another homer in his last at-bat of the same game, off of Doug Brocail. The emergent slugger would make good on those April auspices, posting a ludicrous .333/.476/.647 (137/96 BB/K) en route to his first All-Star appearance and an AL MVP award. His 2001 season was even better: .342/.477/.660 (129/83 BB/K), and though he’d lose out on his second-straight AL MVP award to Japanese sensation Ichiro Suzuki, he’d earned himself a reputation as one of the game’s most feared sluggers. Sports Illustrated had featured the greasy-haired, tattooed Giambi on the cover of their magazine that season, displaying an eerie (if inadvertent) prescience in dubbing him “The New Face of Baseball.” He was unrepentant power, an unforgiving beast of a hitter who eternally threatened to break your team’s back with one swing of his bat.

Giambi homered in his first at-bat of the 2000 season, a deep blast to right field off of Hideo Nomo, and then hit another homer in his last at-bat of the same game, off of Doug Brocail. The emergent slugger would make good on those April auspices, posting a ludicrous .333/.476/.647 (137/96 BB/K) en route to his first All-Star appearance and an AL MVP award. His 2001 season was even better: .342/.477/.660 (129/83 BB/K), and though he’d lose out on his second-straight AL MVP award to Japanese sensation Ichiro Suzuki, he’d earned himself a reputation as one of the game’s most feared sluggers. Sports Illustrated had featured the greasy-haired, tattooed Giambi on the cover of their magazine that season, displaying an eerie (if inadvertent) prescience in dubbing him “The New Face of Baseball.” He was unrepentant power, an unforgiving beast of a hitter who eternally threatened to break your team’s back with one swing of his bat.

He’d also caught the attention of the New York Yankees, against whom he’d played – and lost – in the 2000 and 2001 ALDS. Giambi entered free agency, and the Yankees offered him a monster contract: 7 years, $120 million, with a $22m club option for 2009 and a full no-trade clause, a deal that he quickly accepted. He hit .314 with 41 home runs in 2002, his first season as a Yankee; he earned a Silver Slugger Award and started at first base for the AL All-Star Team.

In 2003, Giambi again hit 41 homers, but saw his average plummet 64 points, down to .250. Ostensibly, there were two reasons for this: he struck out a lot more (his K rate went from 1 every 5 ABs to 1 every 4), and teams seemed to pick up on the fact that he possessed an almost comical inability to hit the ball the the opposite field. Giambi’s BABIP dropped to .263 in 2003 after it had averaged .342 over the previous three seasons. Around that time, it can be presumed, teams started employing “The Giambi Shift,” leaving just the 3B at the SS position and shifting both the SS and 2B to the right side of the infield. This pull-side overload dramatically cut down on Giambi’s ability to profit from balls he put in play. Here’s a quick breakdown of the two “halves” of his career, pre- and post-2003:

| GIAMBI | AB | AVG | BABIP | AB/HR | HR/FB | ISO | OBP | BB/K |

| 1996-2002 | 3782 | .312 | .327 | 17.04 | 20.3%* | .246 | .418 | 0.98 |

| 2003-2008 | 2374 | .248 | .256 | 14.13 | 18.24% | .255 | .397 | 0.86 |

* = FB data only available for 2002

Since the beginning of the 2003 season, Giambi has traded over 60 points in batting average for a slight uptick in raw power, as is measured by ISO and AB/HR. His HR/FB numbers have only seen a slight decrease from 2002, when he was still at the top of his game. You’ll notice, of course, that Giambi played far more regularly over the first half of his career than over the second half. Giambi hasn’t reached the 600 PA plateau since that 2003 season, having been chronically hampered by numerous maladies: foot, wrist, ankle, elbow, and back injuries have all affected Giambi over the past five seasons. Giambi health became the subject of considerable controversy in 2004. That season, he appeared in just 80 games, missing time with what the team claimed was a parasitic infection before being placed on the 15-day DL to undergo treatment for a benign tumor discovered at the base of his pituitary gland. What was the underlying cause of this weird spate of injuries?

Fans and sportswriters were quick to make a connection between Giambi’s fortunes and the biggest news story in baseball at the time: steroids. When discussing the bait-and-switch Giambi’s career seems to have pulled in 2003, it is almost impossible to ignore the potential impact that performance enhancing drugs may or may not have had on the slugger’s career. 2003 was the year that the USADA and the state of California began investigating BALCO for their role in delivering performance-enhancing drugs to professional athletes. Court documents showed that Giambi was a BALCO client. He was subsequently called to testify before a grand jury, after which point his testimony leaked: he’d used several different steroids from 2001-2003. In 2005, Giambi’s brother Jeremy, himself a baseball player who had been named in the BALCO scandal, admitted to past steroid use, effectively incriminating both brothers (Jason had issued a number of very vague “apologies” earlier that year). After dancing around the issue while the media storm swirled and raged, Giambi issued something of a full apology in a 2007 interview with USA Today, around the time of the Mitchell Report’s release:

“I was wrong for doing that stuff […] what we should have done a long time ago was stand up — players, ownership, everybody — and said, ‘We made a mistake.'”

Giambi’s use of “performance enhancers” is no longer open to speculation – he used them, as did any number of his contemporaries, regardless of their stature within the game. The games have all been played, and the numbers have all been tallied and etched in stone for posterity. What remains unclear is whether or not they truly enhanced his performance, and if so, how much. This conversely is a question that remains wide-open for speculation, though there are few (if any) reasonable avenues by which to pursue the answers. Debates rage over identifying the causes of year-to-year variation in performance even in the absence of steroids – when steroid use is added to the equation (and the period of time is not explicitly known), the fingering of cause and effect becomes a speculative witch-hunt.

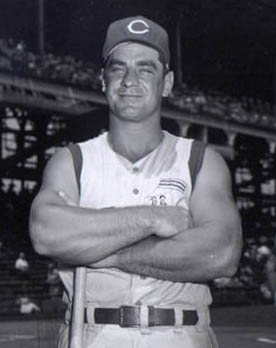

Many, like BP’s Nate Silver, are quick to point to what might be called the Ted Kluszewski Paradox. A football star at  Indiana, “Big Klu” was discovered by a groundskeeper and blossomed into a feared slugger for the Cincinatti Redlegs from 1947-1957. After hitting 74 home runs over the first five seasons of his career, he hit 40, 49, 47, and 35 over the next four seasons – batting over .300 in all of them – before injuries quickly and decisively sapped him of his effectiveness (he was traded to the Pirates in ’58 and was out of the game by ’62). Kluszewski was the prototype: listed at 6’2″ and 225 lbs, the first baseman caused a major uproar in the baseball world when he began sporting a uniform with the sleeves cut off, claiming that his arms were too large for him to swing the bat comfortably in a traditional jersey top. He was joined by greats like Duke Snider, Eddie Mathews, Stan Musial, Willie Mays, and Gil Hodges in leading an era defined by pure, American strength – an era not entirely unlike how the “Steroid Era” was conceived before the scandals broke. There were, of course, no steroids back then: Methandrostenolone (“Dianabol”), the first anabolic steroid available in the U.S., was not commercially produced until 1958. Big Klu was also alone in his bizarre power spike, though it can be speculated that he’d have remained productive had his body not broken down (in the 1959 World Series, after having logged just 223 ABs in the regular season, he famously slugged .826 with 10 RBI in 6 games for the White Sox). He suddenly became a monster at age 28 (Giambi was 29 during his 2000 MVP season), and little explanation exists as to why.

Indiana, “Big Klu” was discovered by a groundskeeper and blossomed into a feared slugger for the Cincinatti Redlegs from 1947-1957. After hitting 74 home runs over the first five seasons of his career, he hit 40, 49, 47, and 35 over the next four seasons – batting over .300 in all of them – before injuries quickly and decisively sapped him of his effectiveness (he was traded to the Pirates in ’58 and was out of the game by ’62). Kluszewski was the prototype: listed at 6’2″ and 225 lbs, the first baseman caused a major uproar in the baseball world when he began sporting a uniform with the sleeves cut off, claiming that his arms were too large for him to swing the bat comfortably in a traditional jersey top. He was joined by greats like Duke Snider, Eddie Mathews, Stan Musial, Willie Mays, and Gil Hodges in leading an era defined by pure, American strength – an era not entirely unlike how the “Steroid Era” was conceived before the scandals broke. There were, of course, no steroids back then: Methandrostenolone (“Dianabol”), the first anabolic steroid available in the U.S., was not commercially produced until 1958. Big Klu was also alone in his bizarre power spike, though it can be speculated that he’d have remained productive had his body not broken down (in the 1959 World Series, after having logged just 223 ABs in the regular season, he famously slugged .826 with 10 RBI in 6 games for the White Sox). He suddenly became a monster at age 28 (Giambi was 29 during his 2000 MVP season), and little explanation exists as to why.

No longer the superstar that the Yankees thought he was when they signed him, the team declined his 2009 option early last October. A free agent for the first time since he left Oakland after 2001, Giambi is set to return to the team that brought him to the majors, having inked a one-year, $5.25m contract to return to the A’s (the club holds an option for 2010). With Jack Cust locked in at DH, Giambi will probably play first base opposite longtime A’s 3B Eric Chavez. Chavez and Giambi played together from 1998-2001; Giambi was just 27 when Chavez broke into the majors as a 20-year-old. The last time they played together (2001), each tallied at least 30HR/90R/100RBI. Giambi will also be reunited with Billy Beane, who became General Manager of the A’s in 1997, then a 35-year old wunderkind. The two traded smiles and jokes at the press conference announcing Giambi’s signing. The latter was distinctly unkempt, clearly paying homage to the attitude that the team embodied at the turn of the millennium, an attitude he hopes to recapture this season after spending seven years as a clean-cut Steinbrenner employee.

Though appearing withered and washed-up under the harsh glare of the Yankee Stadium spotlights, Giambi potentially remains far from his casket. At .247/.408/.534, 96RBI last year, he arguably had a better season than David Ortiz did (.264/.369/.507, 89 RBIs). Ortiz will make $12.5m in 2009 and is, of course, a media darling. Big Papi’s disarming grin and jovial attitude have kept him far from the damning shadows of the steroid issue despite some undue criticism after he attempted to undercut the perceived nefariousness of the problem last year. Ortiz’ comments were made in defense of Barry Bonds: if all the stars had equal access to all the best steroids, why was Barry Bonds still so much better than everyone else? The point was that steroids don’t make the swing, but as the most feared slugger on the planet, Barry’s a special case. Giambi – and those of his ilk – reside in no-mans land between the tarnished elite and the desperate underclass.

It’s interesting, then, that he finds himself in the middle of a small-time feel-good story. His tenure in New York was distinctly unsatisfactory: the Yankees paid him$32,493.91 each time he stepped to the plate, but he managed just three All-Star appearances in his seven seasons with the team. He amassed good power numbers when he was healthy, but he seemed to always be dinged up (he averaged just 528 PA per season) and brought the team no World Series rings: the team only won two postseason series during his tenure (though he did hit two home runs in the infamous Grady Little game). There was the public shame associated with the steroid story – and, being a Yankee, Giambi was predictably vilified by fans and sportswriters throughout the country, who turned his once-beloved greaseball persona into something evil and sinister. When his inner weirdo emerged – during the unsavory Golden Thong Incident, for example, or when he grew out a hideous moustache – it always bore the scent of unfamiliarity, as though this was not what The Yankees, the class of the sporting world, were supposed to be doing (though the Daily News savored every bit, of course). What would Mantle and DiMaggio have thought? The marriage simply never worked.

It’s interesting, then, that he finds himself in the middle of a small-time feel-good story. His tenure in New York was distinctly unsatisfactory: the Yankees paid him$32,493.91 each time he stepped to the plate, but he managed just three All-Star appearances in his seven seasons with the team. He amassed good power numbers when he was healthy, but he seemed to always be dinged up (he averaged just 528 PA per season) and brought the team no World Series rings: the team only won two postseason series during his tenure (though he did hit two home runs in the infamous Grady Little game). There was the public shame associated with the steroid story – and, being a Yankee, Giambi was predictably vilified by fans and sportswriters throughout the country, who turned his once-beloved greaseball persona into something evil and sinister. When his inner weirdo emerged – during the unsavory Golden Thong Incident, for example, or when he grew out a hideous moustache – it always bore the scent of unfamiliarity, as though this was not what The Yankees, the class of the sporting world, were supposed to be doing (though the Daily News savored every bit, of course). What would Mantle and DiMaggio have thought? The marriage simply never worked.

Back in Oakland, though, Giambi can cast off his ill-fitting pinstripes and return to an organization that is eager to accept him. Giambi will almost certainly never bat .300 again: he can’t beat the shift, and can’t hit enough home runs to really nudge his BA upwards. He is still unquestionably a huge improvement to an A’s lineup that lacked an 80RBI hitter in 2008 (Jack Cust’s 77 paced the team), and will form a reasonably fearsome duo in the middle of the order alongside new acquisition Matt Holliday. The A’s scored fewer runs than any other AL team in 2008, and were sorely lacking in any semblance of recognizability (Daric Barton? Jack Hannahan? Dana Eveland?) Giambi should not only outslug anyone from last year’s roster, but he will also give them team a functional emotional leader, a veteran presence who should put fans in the Coliseum’s seats.

Vilification, in some cases, has a funny way of getting turned on its head. After seven seasons spent wandering in the city, Giambi has returned home, and has an opportunity to repair at least part of his damaged legacy. If he can be a productive player for the A’s – and can recapture some of the underdog swagger that he embodied before he left – he stands a chance at becoming something of a folk hero, an evildoer reformed and redeemed in the bright California sun. Some of us get older and start to wonder what our legacy will be. Money can make a man do some pretty awful things – Jason’s still got plenty of it, but maybe he’s been around the block enough times to finally feel like he’s got part of something else to play for, and maybe he’ll run with that. Few will smile and clap as he passes by – fewer still, perhaps, will spit.

January 26, 2009 at 5:10 pm

Jason Giambi is a shithead. No amount of facial hair will change that.

January 27, 2009 at 9:23 am

You crave villains to loathe.

January 27, 2009 at 6:32 pm

I want my World Series in ’03 back.

January 28, 2009 at 8:59 am

UGGGHHHHHHHHHH.

*vomits in mouth*

January 28, 2009 at 2:34 pm

Giambi to Ortiz is actually an interesting comparison. Giambi is Ortiz’s most comparable player through age 32 according to BBRef.com. And look at all of their by age graphs here

http://www.fangraphs.com/comparison.aspx?playerid=818&playerid2=745&playerid3=&position=1BDH&page=0&type=full

They have had very similar careers, and this year will be very interesting for both.

I’ve always though Giambi was underrated in his time in NY, and really only had one bad season (2004). Giambi is a player i’ve always rather enjoyed, and hope he does well in Oakland.

On the flip side I hope Ortiz has a Mo Vaughn like decline, although i imagine it may look more like Giambi’s.

January 28, 2009 at 2:42 pm

Giambi and Ortiz are extremely similar?

Ha. Don’t make me laugh.

You’re forgetting what makes Ortiz so much more valuable than all of his so-called “comparables.”

CLUTCHNESS.