Tim Redding is a goon.

Tim Redding is a goon.

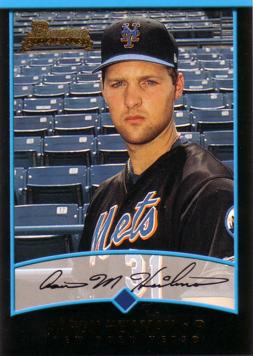

While it is true that a person plucked at random from the street may bristle at being called such a thing, the professional goon, having come to terms with this distinction, is likely to embrace it, albeit quietly. This is especially true for the professional pitching goon. These are your humble practitioners of the boilerplate fastball, your mop-up men and unassuming innings-eaters, artisans of career 4.86 ERAs. Look closely, and they can be found en masse throughout the registers of baseball’s universe. Unable to rise above themselves in any meaningful way, they thrive at their least-noticeable: don’t walk too many guys, don’t let too many pitches drift up in the strike zone, and always – but always – jump over the chalk on your way back to the dugout. Master this art of public anonymity, and a few millions of dollars may flow quietly to your coffers, past rustling reeds of box score notes and a half-dozen Topps cards bearing your likeness.

As anyone who routinely subjects their tendons and ligaments to the unique rigors of baseball-hurling knows, a man is never further than a single pitch away from a new career. As such, walking this thin line for any number of seasons is an impressive accomplishment unto itself. The road is made doubly hazardous by the constant threat of forced obsolescence at the hands of some other set of legs and arms that the ballclub has for whatever reason – youth, reputation, popularity – determined is more worthy of a roster spot than the goon. The replacement player may even be a goon himself. It is probably considered very bad form for the old goon to resent the new; goonery, after all, is something of a fraternity, and while a player may feel betrayed or mishandled, they are advised to address their frustrations to management. A goon may occasion greatness, but this is understood to be a product of chance and circumstance. Those who mistake it for something more are not long for this game.

Born in Rochester, NY, Redding’s major league debut came in June of 2001. Pitching for the team that signed him – the Houston Astros – he made the start against the Cincinatti Reds, a very bad team in the midst of a very bad season (even in the early summer, they were already 15 games back of first place). Sandwiched between two first-inning strikeouts was the dreaded BB-HR; this back-to-back series of events haunts the goon pitcher like no other mortal force on this earth. It is generally not the longball itself that signals the doom of a pitcher: if there’s no one on base, the damage can be limited. If, however, in the time that a pitcher is not giving up home runs they are habitually ushering runners to first base via walks, these homers can add up very quickly.

Tim Redding is, in fact, known to walk a few batters every now and then, which has generally been a problem for him, as he is also partial to giving up home runs. Neither habit has proved grating enough to cause a total jettisoning from the game. Redding threw 182 innings over the course of 33 starts for the Nationals last year, compiling a tidy 10-11 record (the team was 20-13 when he started), including a 3-8 record after the break. The right-hander was thoroughly mediocre all the while. He actually threw his first-ever complete game, though it was of the dreaded 8-inning variety: he lost on the road to the Giants, 1-0, after surrendering the game’s only run in the bottom of the 8th. The 182 innings pitched and 33 games started were both career highs for Redding, eclipsing his 176/32 season of 2003; he earned $125,000 in bonuses on top of his base $1,000,000 contract for his workmanlike efforts. Amongst other pitchers who tossed at least 180 innings last year, Redding’s ERA (4.95) was third-worst and his WHIP (1.43) was eighth-worst. He struck out about 6 batters per 9 innings and walked a little over 3. The 3.21 BB/9 mark was actually the best of his career, which is a nice feather in his cap when considering the fact that he threw more pitches than he ever had before in a professional season.

Being that Redding led the Nationals in Games Started and Wins last season, he was due for a raise in 2009, as an arbitration hearing probably would’ve resulted in a contract worth between $2 and $3 million dollars. The team attempted to trade him prior to the December 12th contract deadline, specifically to the Rockies in exchange for light-hitting OF Willy Taveras. The deal fell through, though, and the Nationals chose to non-tender Redding, making him a free agent. News reports subsequently had him being pursued by no fewer than four big-league teams: The Rockies (now claiming they can’t “afford” him), the Orioles, the Rangers, and the Mets.

Redding would’ve been a poor bet for success in the AL East, a fact which in and of itself makes him entirely qualified to pitch for the Baltimore Orioles. The division isn’t totally foreign to him: in 2005, Redding was traded by the Padres (he’d landed in San Diego that spring) to the Yankees. He took the mound for them exactly once: on July 15th, he started against the Red Sox in a game that Boston would go on to win 17-1 (Redding: 1 IP, 4H, 4BB, 6ER). Not surprisingly, Redding was sent back to AAA the following day; he would not emerge from the minors for two years. So too would it appear he was unfit for service in the nightmarish confines of the Ballpark at Arlington.

Though it’s very possible that Redding had offers on the table from those teams – or others – he recently signed on with the New York Mets, agreeing to a 1-year, $2.25 million contract. If Redding indeed had a choice, he’d seem to have chosen well. Having spent the last two seasons pitching for the Nationals, Redding is already familiar with the opponents he’ll be facing this season; he’ll also be on a much better ballclub than the Nationals were (or will be in ’09) at double the salary he was earning from them. A native of New York, he’ll be pitching a cross-state drive from where he grew up.

In 11 career starts against the Phillies, Redding is 5-3 with a 3.29 ERA. While it is highly irresponsible to spend millions of dollars chasing splits and past performance, such is the nature of business within the game; Redding’s successes against the Mets’ bitter divisional rival were not lost on his new ballclub. Slice even the most piecemeal of men thinly enough, and you’re likely to notice a significant-looking tendril or two that leads you toward a conclusion that the humble gentleman before you is ill-equipped to realize. The Mets are still in pursuit of Oliver Perez and Derek Lowe at the very least; if they land one, Redding’s spot in the rotation is not guaranteed.

Even if Redding starts the year in the bullpen, he’ll still provide rotation depth for Jerry Manuel’s contingent of underachievers. Depth, at the end of the day, is the one asset that the professional goon possesses the greatest quantities of. Shouldering these unseen stores is no Herculean task, which is fortunate, as those of Redding’s ilk could nary please us were they handed such instruction. If Maine, Pelfrey, or any of the other rotation stalwarts miss time, the Mets will be able to draw upon the wells of this depth that are locked within Redding’s trademark goatee and modest sneer. He will grunt and hurl his most earnest of fastballs, pick up the pieces where they lay, and live to collect another paycheck, until the teams stop calling and he assumes his place in the vast unseen pastures where the Paul Wilsons of the world chew long stalks of grass and melt seamlessly into the bygone tapestries that faithfully measure out the interminable passage of time.